Offered for sale are

A 1944 HANDWRITTEN AND SIGNED CURRICULUM VITAE AND A 1944 MEDICAL EVALUATION OF

SS-UNTERSCHARFÜHRER EDUARD ROSCHMANN

HE WAS KNOWN AS THE ‘BUTCHER OF RIGA’ AND BECAME EVEN MORE INFAMOUS AFTER THE RELEASE OF THE MOVIE ‘THE ODESSA FILES’

FULL MONEY BACK GUARANTEE FOR AUTHENTICITY

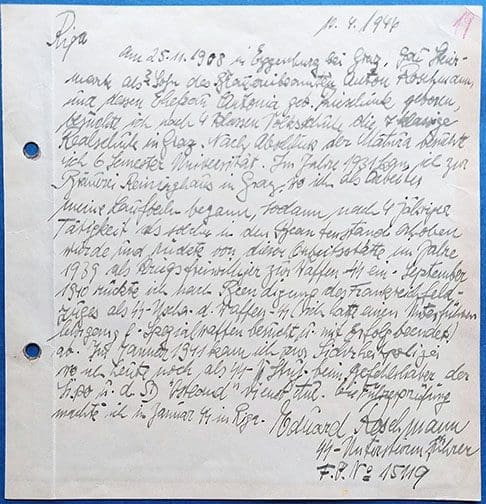

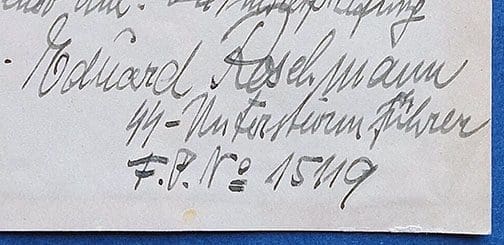

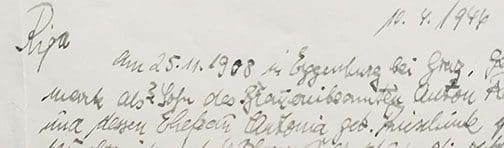

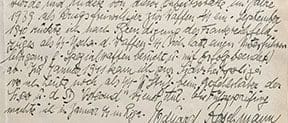

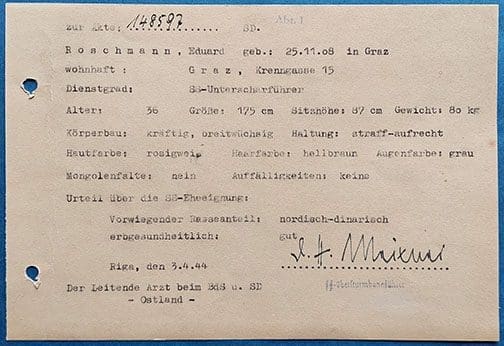

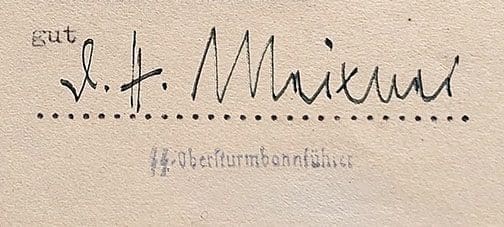

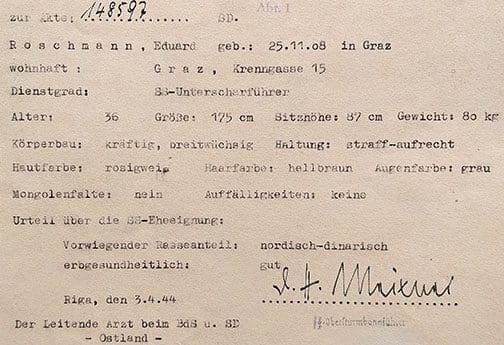

Handwritten curriculum vitae by the hand of SS-Unterscharführer Eduard Roschmann, better known as the ‘Schlächter von Riga’ (Butcher of Riga) and the movie ‘Die Akte Odessa’ (The Odessa Files). Anything signed by Roschmann is as rare as it gets and never offered anywhere and a handwritten ‘Lebenslauf’ or curriculum vitae, especially one that is dated so late in the war is definitely an unique find. His ‘Lebenslauf’ contains his entire SS career and his 1944 address is Feldpostnummer (Field Post Nr.) 15119, which is the address of the High Command of the Sicherheitspolizei and SD in Riga. The second document is a medical evaluation by the chief physician of the SD Ostland, SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Hanns Meixner, dated 3 April 1944 (7 days before Roschmann wrote his curriculum viate) and signed by him in ink. Dr. Meixner attests that Roschmann is of Nordic race and meeting all racial requirements for a SS sanctioned marriage.

We have never seen or heard of another pre-1945 document signed by the ‘Butcher of Riga’, SS-Unterscharführer Eduard Roschmann.

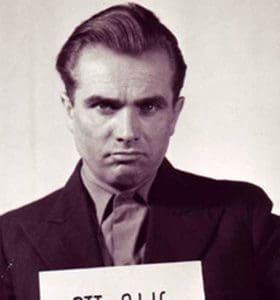

Eduard Roschmann (25 November 1908 – 8 August 1977) was an Austrian Nazi SS-Obersturmführer[1] and commandant of the Riga Ghetto during 1943. He was responsible for numerous murders and other atrocities. As a result of a fictionalized portrayal in the novel The Odessa File by Frederick Forsyth and its subsequent film adaptation, Roschmann came to be known as the “Butcher of Riga”.

He joined the civil service in 1935. In May 1938, he joined the Nazi Party NSDAP Number 6,276,402, and the SS the following year. In January 1941, he was assigned to the SD. Following the German occupation of Latvia in the Second World War, the SD established a presence in Latvia with the objective of killing all the Jews in the country. To this end, the SD established the Riga ghetto. Men, women and children were forced into the ghetto, where at least for a short time they lived as families. On 30 November and on 8 December 1941, 24,000 Jews were force-marched out of the ghetto and shot at the nearby forest of Rumbula. Except for Babi Yar, this was the biggest two-day massacre in the genocides until the construction of the death camps in 1942. In March 1942, the German authorities in charge of the Riga ghetto and the nearby Jungfernhof concentration camp murdered about 3,740 German, Austrian and Czech Jews who had been deported to Latvia. The victims were mostly the elderly, the sick and infirm and children. These people were tricked into believing they would be transported to a new and better camp facility at an area near Riga called Dünamünde. In fact no such facility existed, and the intent was to transport the victims to mass graves in the woods north of Riga and shoot them. According to a survivor, Edith Wolff, Roschmann was one of a group of SS men who selected the persons for “transport” to Dünamünde. (Others in the selection group included Rudolf Lange, Kurt Krause, Max Gymnich, Kurt R. Migge, Richard Nickel and Rudolf Seck). Starting in January 1943, Roschmann became commandant of the Riga ghetto. Historians Angrick and Klein state that in addition to the mass killings, the Holocaust in Latvia also consisted of a great number of individual murders. Historians Angrick and Klein state that in addition to the mass killings, the Holocaust in Latvia also consisted of a great number of individual murders.

‘… the reading provided by witness accounts … makes it clear that the genocide in occupied Riga consisted of an enormous number of individual murders in addition to the large-scale operations. The image of the Holocaust in Latvia conveyed in these reports is not that of a gigantic impersonal killing machine, even if the plans for shooting the Jews of Riga in winter 1941 conjure up a process of mass murder based on division of labour. The overall pattern in these accounts is dominated by individual murders committed out of a desire to kill, punish or deter.’ Angrick and Klein name Roschmann among others as responsible for these individual murders. Roschmann, together with Krause, who, although no longer ghetto commandant, was close at hand as the commandant of the Salaspils concentration camp, investigated a resistance plot among the Jews to store weapons at an old powder magazine in Riga known as the Pulverturm. As a result, several hundred inmates were executed. Roschmann was later transferred to the Lenta work camp, a forced-labor facility in the Riga area where Jews were housed at the workplace. Roschmann participated in the efforts of Sonderkommando 1005 to conceal the evidence of the Nazi crimes in Latvia by exhuming and burning the bodies of the victims of the numerous mass shootings in the Riga area. In the fall of 1943, Roschmann was made the chief of Kommando Stützpunkt, a work detail of prisoners which was given the task of digging up and burning the bodies of the tens of thousands of people whom the Nazis had shot and buried in the forests of Latvia. About every two weeks the men on the work detail were shot and replaced with a new set of inmates. Men for this commando were selected both from Kaiserwald concentration camp and from the few remaining people in the Riga ghetto. In October 1944, out of fear of the approaching Soviet armies, the SS personnel of the concentration camp system in Latvia fled the country by sea from Riga or Liepāja to Danzig, taking with them several thousand concentration camp inmates, many of whom did not survive the voyage. In 1945, Roschmann was arrested in Graz, but later released. Roschmann concealed himself as an ordinary prisoner of war, and in so doing obtained a release from custody in 1947. After that however he became imprudent and visited his wife in Graz. He was recognized with the assistance of former concentration camp inmates and arrested by the British military police. Roschmann was sent to Dachau concentration camp which had been converted to an imprisonment camp for accused war criminals. Roschmann succeeded in escaping from this custody; in the process while running in hiding from a British patrol at the Austrian Border he was shot through the lung and also lost two toes of one foot to frostbite. In 1948 Roschmann was able to flee Germany. He travelled first to Genoa in Italy, and from there to Argentina by ship, on a pass supplied by the International Red Cross. Roschmann was assisted in this effort by Alois Hudal, a strongly pro-Nazi bishop of the Catholic Church. In 1968, under the name “Frederico Wagner” (sometimes seen as “Federico Wegener”) he became a citizen of Argentina. In 1960, the criminal court in Graz issued a warrant for the arrest of Roschmann on charges of murder and severe violations of human rights in connection with the killing of at least 3,000 Jews between 1938 and 1945, overseeing forced laborers at Auschwitz, and the murder of at least 800 children under the age of 10. However, the post-war Austrian legal system was ineffective in securing the return for trial of Austrians who had fled Europe, and no action was ever taken against Roschmann based on this charge. In 1963, the district court in Hamburg, West Germany, issued a warrant for the arrest of Roschmann. In October 1976, the embassy of West Germany in Argentina initiated a request for the extradition of Roschmann to Germany to face charges of multiple murders of Jews during the Second World War. This was based on the request of the West German prosecutor’s office in Hamburg. The request was repeated in May 1977. On 5 July 1977, the office of the President of Argentina issued a communiqué, which was published in the Argentine press, that the government of Argentina would consider the request even though there was no extradition treaty with West Germany. Roschmann then fled to Paraguay. Roschmann died in Asunción, Paraguay, on 8 August 1977. The body initially went unclaimed, and questions were raised as to whether the dead man was, in fact, Roschmann. The body bore papers in the name of “Federico Wegener”, a known Roschmann alias, and was missing two toes on one foot and three on the other, consistent with Roschmann’s known war injuries. Emilio Wolf, a delicatessen owner in Asunción who had been a prisoner under Roschmann, positively identified the body as Roschmann’s. Simon Wiesenthal, however, was skeptical of the identification, claiming that a man matching Roschmann’s description had been spotted in Bolivia only one month earlier. “I wonder who died for him?” he said. A fictionalized version of Roschmann was given in Frederick Forsyth’s novel The Odessa File. A film version of the novel was released in 1974, where Roschmann was played by Austrian actor Maximilian Schell. In the book and the film, Roschmann is portrayed as a ruthlessly efficient killer. Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal was portrayed in the film by actor Shmuel Rodensky. Wiesenthal was using the thriller to force Roschmann out into the open, which is what actually happened. Roschmann was eventually identified and denounced by a man who had just watched The Odessa Files at the cinema. [source: Wikipedia]

This item ships from one of our affiliates in Germany. Includes shipping worldwide.

This document duo ships from one of our affiliates in Germany. It comes from a private collection and has never been offered for sale before. It was purchased directly out of a German archive. The seller gives a full money back guarantee for the authenticity of the document and signature. Includes shipping worldwide.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.